An engineer who frequently travels for her job, suddenly finds herself in airports other than the one she arrived in…

When she got off the plane, Amelia was thinking about her boyfriend, Jerome. They’d been arguing about the laundry.

“If you want me to do the laundry, just tell me to do it!” Jerome had said. They’d been together for six years. During the pandemic they’d bought a townhouse in South Austin and were now in huge joint debt, plus Amelia’s student loan. They’d been talking about marriage, but really, they didn’t have to get married to be completely bound to each other.

She was walking down the concourse, past gates. For a moment she thought, Where am I? So many airports. Right, she was at Dallas Fort Worth, which honestly was a pretty distinctive airport, but airports tended to look more like each other than they did the place where they were. The gates were some combination of blue and gray and white. The shops might be different from airport to airport but they all had to be laid out pretty much the same. She flew through Dallas a lot for work. That day, she was headed to Madison, Wisconsin, to sooth a client who had fears about the fire in the LED installation on the Tallin Building in Atlanta and wanted assurance that the installation they were doing on their building wasn’t going to catch fire.

She was in Concourse C and the connecting flight was in A. The airport wanted everyone to take the inter-airport monorail, but she was at the end of the concourse and to get the train she’d have to go back to the middle. She was right next to a corridor that connected the two concourses, so it was shorter to just walk across. And she’d get steps.

Her mind went back to Jerome. The pandemic had been tough. They were both working remote. She loved him, she really did. But sometimes she didn’t know how she was going to spend the rest of her life with someone who couldn’t see an overflowing laundry basket. She didn’t wait for Jerome to tell her to clean the bathroom. It was a chore. You do chores when they need to be done. When she saw the bathroom needed cleaning, she might put it off for a couple of days because, you know, bathroom. Then she buckled down and did it. She didn’t run to Jerome and tell him, either. Jerome always announced, “I’m doing laundry.” And “If you hear the dryer buzzer, tell me.” “And I did laundry.” Like every time he did something, he was supposed to be praised.

She resisted the impulse to offer him a medal. She knew that lots of people had partners who didn’t do anything. Or who gambled or drank or something. Jerome was a great guy; at least he was willing to do laundry. But damn it, she didn’t mention when she did the bathroom. Or planned dinners for the week. Or went grocery shopping.

The connecting corridor was without windows. Truly, she could have been in almost any medium or large airport in the U.S. Blue signs with white lettering, polished gray floor. Mostly empty at the moment, between waves of arrivals and departures.

Thinking about Jerome was probably why she wasn’t really paying attention. That and the fact it was an airport. She knew and understood the method and rhythms of airports. She kind of thought the corridor seemed longer than she remembered (thank God she had an hour and twenty minutes between connections). There was a broad corridor going off to the left that she definitely didn’t remember. It shook her out of her ruminations. She peered down the length of it and could see it opened up onto another concourse. It was running at right angles to the other concourses. But it couldn’t—there wasn’t room for a terminal there, there were buildings and roads and stuff. It was like finding there was a room in her townhouse where the townhouse next door should be.

She had a good mental map of Dallas Fort Worth. It was like three doughnuts on a stick. She was in the center of the airport structure, the stick, and all the gates were around the edges of the doughnuts because, of course, planes had to land, and they pulled up to the outside of the airport. This shouldn’t have had gates; the planes shouldn’t have been able to pull up. It didn’t look right—it was a big open space, white with big windows. It looked like an airport, but it didn’t look quite like Dallas. Airports looked a lot alike, but if you spent a lot of time in them, there were familiar things, and it didn’t feel like Dallas. For one thing, it looked new. Which obviously it was.

She had time. She walked down the corridor. As she got farther down, the noise got louder, clearer. Busy airport noise.

It was a concourse. She’d never seen it before. But it was obviously open. There were gates and restaurants. She couldn’t figure out the gates. She pulled out her phone to see if she could find out where they were and her phone said it was an hour later, that she had just fifteen minutes to get her flight. Which made no sense.

Then it asked her if she wanted free Wi-Fi from the Charlotte Douglas International Airport.

Wait, she was at Dallas Fort Worth. She was headed to Wisconsin. She called up Google Maps and it put her right square in the middle of Concourse C in Charlotte, North Carolina.

She was having some kind of psychotic break. Nervous, she walked back down the corridor and called Jerome.

“Hey babe,” Jerome said, easy, and picturing him, his glasses, his long hands, dark skin and pale beautiful nails, his voice calmed her a little.

“Hey, what day is it?” she asked.

“Tuesday,” he said. “The day you go to . . . um . . .” She could picture him leaning to see his calendar. “Go to Wisconsin.”

“Yeah,” she said. “About that. I think I’m in Charlotte.”

“What?” he asked. “Wait. How are you?”

She was at the T to the shortcut that she’d taken in Dallas. It was still empty. Honestly, what she should have done was check her boarding pass, see if she had some clue how she got here. She left Austin this morning; even if she got on the wrong plane, she shouldn’t be in Charlotte. “What time is it?” She pulled her phone from her ear and checked the time.

It wasn’t almost one o’clock, she had an hour and fifteen minutes to get to her gate. She’d gotten her hour back.

“It’s almost noon,” he said, which meant she was in the same time zone he was. She was back in Texas. “Are you okay?”

“Yeah,” she said. She checked Google Maps. She was in Dallas Fort Worth. She looked behind her. She could still see the place she thought was Charlotte. “Shit, never mind,” she said. “I think I’m traveling too much.”

“Just don’t become George Clooney,” Jerome said. “Hey, if you’re not all right, I could drive up there and get you.”

“No, no,” she said. He was such a good guy. Except for the laundry-blindness thing. And the fact that sometimes instead of listening, he tried to fix things. She was an engineer, she was perfectly capable of fixing things; sometimes she just wanted to talk. “You know all airports look alike,” she said. “I just saw a restaurant that I thought was in another airport.”

“Legal Sea Foods?” he said hopefully. They’d eaten there in Philadelphia airport and he loved the chowder.

“Nah,” she said. After they ended the call, she walked back to the Charlotte place, only this time she held the phone in her hand. She was halfway down the corridor when the time shifted from Central to Eastern.

She stopped and checked Google Maps. She was in Charlotte.

What if the way back stopped taking her to Texas?

She felt so scared she felt sick. She jogged back to the T in the corridor. Back in Texas, according to her phone.

Now she was truly freaked. She walked to her gate.

She sat at the gate. She got up once to see if the corridor to Charlotte was still there but stopped and sat back down, afraid she’d miss boarding or something.

Or just afraid.

She flew to Madison. The airport in Madison was nice, not too big. Blues, grays, anonymous.

She didn’t connect through Dallas on the way back so she couldn’t check again. But she thought about it a lot.

It was impossible, which meant there was something else going on. She was experiencing psychosis, or false memory. Or she had dozed at the gate and dreamed it. Travel did things to people. Strung them out, disoriented them, exhausted them. When she dozed on the hop to Austin, she dreamed of corridors and gates, and giant shiny pinballs rolling through them, which shook her awake.

And then it was the holidays, and she didn’t fly anywhere for two glorious months.

She flew again at the end of January. Headed to support one of the sales guys on a pitch in Pittsburgh.

She wasn’t even thinking about the weird Dallas thing when her flight landed late in Chicago. Chicago was always a disaster. She had calculated that she missed about half her connecting flights going through O’Hare, but it rarely mattered because she just found a kiosk and rescheduled, often for an hour later. This time, when she rebooked, she had a three-hour layover. Which seriously, she didn’t mind. She sent a text to Pittsburgh, telling Seth, her coworker, that she’d been rescheduled and would be late.

There were shops and restaurants. Why did so many airports have navy blue carpet at their gates? Was blue supposed to represent the sky? Freedom? She’d read that blue was calming, which, God knew, airports needed these days.

But she could always use the steps. She tried to get the magic ten thousand even though she knew that the number wasn’t nearly as meaningful as they all thought. Walking was better than sitting.

Chicago was crowded. (Chicago was always crowded.) She dodged and weaved, seething silently at the family all walking abreast toward the gates at the end of Concourse H, taking up the whole freaking walkway except for just enough width for one or two people to pass them on the right. Self-absorbed tourists with no sense of courtesy or airport etiquette. Walk like you drive, she thought. Stay to the right, look before you dart through the sea of people. Give a rat’s ass. Everyone around you is people, not obstacles, things.

She saw a service door open and another walkway. It didn’t look like the back areas of airports, which tended towards the industrial. It had blue walls and was shiny and front-facing and was running parallel to this walkway, so she stepped through.

Most people, like her, must not have known about this area. There were fewer people in the concourse and at the gates, and she felt calmer just because it all was less frantic. She checked her steps. 3,298. She passed the Great Lakes Brewing Company and noticed that this was Concourse C? Which was impossible because Concourse C was on the other side of O’Hare. She walked toward baggage and things felt—off. She pulled out her phone.

Her phone thought she was in Cleveland. She was in Cleveland Hopkins Airport. She walked back and saw the service door to Chicago. People passed it without seeming to notice. She stepped into Chicago. No one seemed to register either the door or that she just appeared.

She stepped back into Cleveland. She could feel the difference. Cleveland felt less overwhelming. The whole vibe of the airport felt different. Less frantic. Less noise. The carpet at the gates was gray instead of blue, but the pillars were navy.

Part of her said that she needed to jump back to Chicago before the door closed or disappeared or whatever.

But what was the worst that would happen? If she got stuck in Cleveland, she just walk out through baggage claim and then go buy a ticket to Pittsburgh.

Or maybe she was in some sort of fugue state and was actually wandering around Chicago in a daze. It didn’t feel like she was. She checked the date; it was the right date to be flying to Pittsburgh. Seth, maybe one of her least favorite sales guys, was waiting for her to come in and answer questions about how they could do an installation on a building on the National Register of Historic Places (which meant there were rules about drilling into the façade). She hated the project because the only way they could secure scaffolding to install the frames that held the LED panels was to drill into the mortar between the sheets of Pennsylvania limestone that covered the façade, and she was worried about safety. But the higher ups had sold the company on LEDs and she was supposed to make it work.

Being in Cleveland was kind of the least of her problems, right? Hell, from Cleveland she could rent a car and drive there in less than three hours, which was a lot less time than it would take her to fly. But what would happen when she didn’t show up for her flight in Chicago?

What could happen? People didn’t show up for flights all the time. It wasn’t like the airlines cared. Some poor sod would get her seat and their day would be made 100 percent better. She walked down the concourse, thinking. Did she have the nerve? This really didn’t make any sense. She should be freaked out. But it always felt like airports were liminal spaces, not really local, not really not. She saw a place to eat called Bar Symon. On a whim, she went in and sat down.

It was nice. She ordered pierogies and kielbasa—she didn’t eat much meat, but she thought pierogies sounded interesting. She didn’t google them. She ordered a beer, too, another thing she rarely did, especially during the day because day drinking made her tired and made the rest of the afternoon feel like forever. The beer was good. The pierogies were tasty. Sort of a cross between an Asian dumpling and a knish, filled with mashed potatoes and cheese. She paid with her credit card and got an alert on her phone immediately asking if this was fraud. She said NO.

She wasn’t sure if she felt exhilarated or terrified. Would the credit card company figure out that she couldn’t possibly be in Cleveland?

The server brought the check and receipt, and Amelia almost left the receipt because she couldn’t think of turning it in on her expense account. But it was tangible. It was proof.

As she walked back toward the door, she became convinced that it was closed or gone or something. She really didn’t want to rent a car she couldn’t explain and drive to Pittsburgh. She’d have to pay out of pocket because she couldn’t expense it, and they’d just bought a new couch and they put it on a credit card, and she didn’t want another big purchase. But mostly because it felt weird. It occurred to her that they’d bought an airport–navy blue couch. She was definitely traveling too much.

The door was still there, and she couldn’t help breaking into a jog, and then walked through. The noise of Chicago O’Hare hit her like a low-pressure system—pervasive, but familiar. Thick. Go back, something said, but she didn’t.

She kept the receipt in her wallet. It was a talisman. She kept her eyes open. She flew to Pittsburgh again for the installation of the screen. The façade of the building had to be tuck-pointed and brought up to code, but the screen was designed to fit the old façade. Construction crews didn’t work to engineering tolerances. The building wasn’t square to a quarter inch, much less the tolerances of the LED frames. Years had shifted it, not enough to be problem, but enough to make construction complicated. “A building like this,” one of the masons said, “she’s an old lady.” He laid his hand flat against the stone. “She’s got opinions.”

She had installers seventy feet up the side of a building on scaffolding that couldn’t be secured to the façade because the building was on the National Register of Historic Places. Pennsylvania limestone cladding, quarried in the state. The façade was a nightmare. It didn’t feel safe enough.

She adjusted the frames for the LEDs, and she asked the mason about angling the brackets. She knew he’d say, “It won’t work,” and he did. She mused out loud to the mason about floating them off a frame hung over the lip of the roof, about how long it would take to fabricate it, about shutting down the job until they find a solution.

The mason rose to the bait. He suggested a way they could mount the brackets at an angle, driving supports in at the masonry joint, which they were allowed to do.

“You’re a smart cookie,” he said, and winked at her.

She smiled back, thinking about airports.

At the Pittsburgh Airport, there were no secret doors or unexpected corridors.

She didn’t travel for a couple of months, and then it was late spring, and she was off to Denver, Colorado.

No secret corridors. No doors to another space.

Oh, the job was interesting. The North Face (the people who made parkas and stuff) wanted to build a curved interactive LED screen in their lobby. She went back twice over the summer, and then flew to Sea-Tac for another pitch in Tacoma. They didn’t get the Denver job, but she brought Jerome North Face swag—a polo shirt and a pair of Smartwool socks. She dressed like an engineer, awkward and practical, but Jerome liked clothes.

By Thanksgiving, she concluded that when she brought the receipt back from Cleveland she broke something.

Broke something. Not like dropping-her-phone breaking something, more like surface-tension breaking something. Like she had been skittering across space like a water bug, and the weight of the receipt was too much and broke the surface tension.

She was home in their townhouse, which, despite their touches, she was beginning to think of as like a lot of other two-story townhouses, stuck in a row of identical studios and one- and two-bedrooms. The carpet was contractor-grade off-white. The bathroom fixtures and the cabinets were serviceable, but looked like the fixtures and cabinets in Boise, Idaho, or Norfolk, Virginia. Maybe it was good that she broke the surface tension. What if she found a door in their townhouse that led to another townhouse? What if someone was living there? It could all get awkward and weird. She got anxious in the bathroom, expecting a stranger to walk in.

Jerome worked from home four days a week. She worked three days at home, and two days in the office. The two overlap days were difficult. Jerome claimed the bedroom, and they’d put a desk in there. She worked downstairs and dealt with insistent cats—convinced that because she was home, she needed to pay attention to them—and Jerome’s frequent trips to the kitchen for coffee.

Jerome clattered in the kitchen. Faces stare at her from the computer. The virtual panopticon. She finished the meeting and shut it down.

“How’s it going?” Jerome asked.

“Same old, same old.” She couldn’t explain why she said suddenly, “I had a really weird experience last year.”

“What?” Jerome asked. He was so amazing. Tall, lanky, smart. She was pretty sure he was out of her league.

“I, ah, was in the airport, Dallas Fort Worth, and I found this corridor, you remember? I called you…”

“Yeah?” he asked. He didn’t remember. Not his fault; why would he remember a random conversation. He sipped his coffee.

“And I thought it was, like, a shortcut. Between the terminals. That it would be faster. But it took me to Charleston.”

He waited, clearly not understanding.

“One minute I was in Texas. The next I was in North Carolina. You know, NASCAR, the whole nine yards.”

“You got on the wrong plane?” he asked. She could see him racking his brain, trying to remember when this might have been.

“No,” she said. “It was a corridor, connecting the two airports.”

“I don’t understand,” Jerome said. He had been listening, Jerome often tried really hard to listen, which made her feel like she was imposing, but now he was listening.

“Me neither,” she admitted. “I mean my phone said it. I was there. And then I walked back down the corridor and caught my plane. From Dallas. And it happened again, when I was flying to Pittsburgh. I was in Chicago and I saw a door and another concourse, and I, you know, went and looked and I was in Cleveland.”

“Amelia,” he said slowly, “I don’t know what you’re trying to say.”

“It happened!” she said. She dug through her wallet and pulled out a receipt. “Here, look.”

He studied it. She loved his hands. He had large, beautiful hands, palm-a-basketball-sized hands, and since he was tall and black, was always being asked if he played basketball. He did not, in fact, play basketball. He hated the outdoors, hated organized exercise, grudgingly did yoga because he had back problems and his doctor had said, “Do yoga now or have back surgery at fifty.”

He was studying the receipt. “You got this when you went through the door? To Cleveland?”

“Yeah,” she said. “I had lunch in Cleveland, and then walked back through the door to Chicago and flew to Pittsburgh.”

“I don’t get it,” he said.

“Me neither. But now it doesn’t happen anymore, so it doesn’t matter.” Her own bitterness caught her by surprise.

“What doesn’t happen?”

“The spaces. The door, the corridor. After I brought back the receipt, it stopped.”

He came over and sat down on the ottoman they used as a coffee table. He was wearing his fancy North Face socks and no shoes. “Ame, you’re scaring me.”

“Look!” She pulled up her calendar and scrolled back to the Pittsburgh flight. “Look. I was in Chicago. I missed my connection and scheduled a later one. Then I had lunch in Cleveland. See? It’s on the receipt. Cleveland Hopkins Airport.”

Jerome frowned in concentration, looking at the calendar. Then the receipt. “You did this. You walked through a door, and you were in another airport.”

“Yeah,” she said.

He studies her calendar. “I don’t know what to say. Why didn’t you say anything?”

“The first time, I thought I’d fallen asleep at the gate or something.” And it sounds crazy, she thought. “I thought you would think I was psychotic. I thought I might be.”

“And now you can’t do it anymore?” he asked. “You just, like . . . know it?”

She shrugged. “I don’t know how to test it, empirically.” Honestly, she didn’t know anything.

They talked about it and then Jerome had to go upstairs and work. They talked about it some more that night in bed, turning it over between them. (Jerome liked talking after the lights were out. Or in the car. He said it was a guy thing.) They talked about it some the next day, sitting at their kitchen table eating take-out burritos, handing it back and forth like a smoothly worn stone. And then they ran out of things to say. There had never been very much to say about it anyway.

It became a thing in the background. Something that had happened. Better than a secret, Amelia thought. Secrets were toxic.

Austin to Dallas to London. She drove to the airport in the rain.

It was an exciting possibility, working with Dua Lipa’s people to create a screen for her concert. Most of this kind of work was handled by a few big entertainment engineering firms. This time, it was Taylor-Halston in London. They had too much work and were looking for a subcontractor. Getting into entertainment was a new revenue stream. The boss was in London pitching the project, and Amelia was flying out to meet him to say engineering things about fire-retardant plastics and installation.

She was thinking about the challenges. Big-venue music concerts had complicated rules. Everything had to go together without tools because that way the guys assembling the stage set couldn’t drop a hammer or a wrench on someone by accident. It had to all break down to fit in a tractor trailer to be driven to the next city, the next stadium, the next concert venue, and set up in forty-eight hours. She was thinking about strapping, which was part of the assembly, when she saw a hallway. The hallway was a maintenance hallway, the kind you normally only catch a glimpse of as someone who works at the airport either appears out of it or disappears into it, but this was just standing open and she could see the short hallway and where it ended.

She turned sharply right, cutting across the concourse.

“Hey!”

It was a woman, maybe late thirties, standing near the hallway, holding a coffee.

“Sorry,” Amelia said. “Is it restricted?”

“No, it’s just that you noticed it.” The woman walked over. “I notice them, too.”

Amelia got goose bumps on her arms. “You’ve done it?”

“Yeah. Yeah. Lynne.” She stuck out her hand. She was brittle-looking, her face pinched. Her hair was loose and a little messy.

“Amelia. You . . . do you know how it works?”

Lynne looked confused. “What do you mean?”

“I don’t know. Do you find them every time you go to an airport?”

“I didn’t at first,” Lynne said. “You have to not think about them. I mean, you have to want the destination, but not think about it. I can’t explain it. I mean, that’s how it works for me, I think.”

Like Dostoevsky said, the hardest thing to do is to make yourself not think of a large white bear. Just tell yourself not to and it’s all you can think about.

“Is it random?” Amelia asked.

Lynne shrugged.

“I mean, what airport connects to what. Does Dallas always connect to Charlotte?”

“Not for me,” Lynne said. “Greg said it mostly stayed the same for him.”

She was an engineer, problem-solving.

Greg? “There are others?” Amelia asked.

“There are,” Lynne said. “I’ve met three others, you’re the fourth. Two of the others are women, and I’ve only seen them once, both in Denver. Greg, I’ve seen him three times. I think he does this a lot or something.” Lynne said she could kind of get close to the airport she wanted. She’d wanted Houston and Austin. She’d come here through the door trying for Houston or Austin and gotten Austin.

Okay, Lynne could kind of control it?

“Do you always get close?” she asked Lynne.

“Sometimes,” Lynne said. She looked uncomfortable.

Amelia wanted to know how often she traveled, how often she got close. She wanted to plug this into Excel, get a feel for it. People were terribly unreliable, but numbers were better. Still, Lynne didn’t look like she wanted to be interrogated about how often she flew, how often she found doors and corridors, how often she got close.

Lynne pointed to the door Amelia had seen. “It goes to JFK. You might be able to get to London from there.”

Amelia had forty minutes until her plane boarded. She gave Lynne her business card. “Email me?”

Lynne didn’t seem to want her business card. “I’ve . . . um, never . . . um.” Amelia really wanted to go through the door to JFK. Lynne stumbled through trying to explain something. “I never, I mean, the other people, you know . . . except in airports . . .”

“Email me?” Amelia said. She didn’t think Lynne ever would.

JFK was blue, white, and gray, sound echoing off hard surfaces. She glanced back. Lynne was still visible through the doorway, clutching her coffee. She still had that pinched look.

It was almost 5:00 p.m., Texas time. Amelia never flew into JFK after noon. Arriving international flights got priority for runways (because, Amelia supposed, no one wanted to run out of fuel over the Atlantic). If there was weather anywhere up and down the East Coast, or any other reason for a delay, getting out of JFK was a nightmare. But she wasn’t flying out of JFK.

She had to stop thinking about it. She should have asked Lynne if she should do anything to get the way to open to London. Think about London?

She paced, pulling her roller bag, looking at the terminal, making herself notice the restaurants and shops. Hudson News. She should get something, get a receipt to show Jerome. She could call him. It felt weird to call someone, like this was her secret and if she told someone it would break the spell or something. But no secrets, she didn’t like keeping secrets. They were like a wound, they got infected, then they spilled infection everywhere. She called him.

“Hey, babe,” Jerome said. “What’s up?”

“I’m at JFK,” she said.

Brief pause, then, “You hate JFK,” he said.

He didn’t realize what it meant.

“No, I was in Austin and then I, I walked through a door and now, here I am!”

“Wait, what?”

“You know, like I told you, about airports. The receipt from Cleveland Airport.”

Then he caught it. “Holy shit, are you kidding?”

“Hold on,” she said. She took a photo of the arrivals/departure board. “I sent you a picture,” she said. “You see the flight departing for Austin? I’m in New York!”

“You said it didn’t work anymore!”

“I know!” She could feel all the excitement bubbling up in her. “I KNOW!”

“Wow,” he said. “Think you could get to London? Does there have to be a flight from the airport you’re at to the airport you want to go to? I mean, it’s JFK, so there’s flights to London.”

“I don’t know! I don’t know how it works! I met another person, a woman, who sees the doors and corridors, too. The woman I met said one guy could sort of go where he wanted but I don’t know if it’s true. I should have talked to her more!”

She kept him on the phone, chattering, sending pictures. She found a sign that said JFK was renovating Terminal 4. coming in 2023, a $1.5 billion renovation and expansion of terminal 4!

“You gotta buy me something,” Jerome said. Jerome dressed impeccably, even when working from home. Tech-bro button-downs, a four-hundred-dollar pair of Grigio Suede Milano loafers that he may have loved more than he loved Amelia (but not more than the cat, thank God). “You want a T-shirt that says ‘I love New York’?” she asked. “A shot glass?”

“Anything,” he said. “Are you looking for a way to London?”

“I don’t think it works that way. Lynne said you can’t think about it,” she said. “I mean, I’m not sure, but after Cleveland I kept looking but I didn’t find one until I stopped. I don’t know if the guy who says he can kind of get where he wants was telling the truth. I mean, I never met him, or anyone other than that woman.”

She bought the worst NY touristy T-shirt she could find—she’d make him wear it to sleep. She had to pee and there was a line but she was so energized, she didn’t care. She FaceTimed Jerome after that so he could see.

He kept saying, “This is wild.”

Then he said, “When’s your flight?”

She had another hour, but it was time to go back.

The door was gone.

“Maybe you just missed it,” Jerome said. “It’s okay, babe.”

She was panicking. Her heart was pounding. “I’m so stupid,” she said. “God, I’m so stupid.”

“Take a breath,” Jerome said. “It’s okay. Take your time.”

She looked for the door. She looked for Lynne. “Maybe it was Lynne’s door,” she said. “Maybe she already came back and it closed. Stupid! So stupid.”

“Seriously,” Jerome said. “It’s okay. Hold on.”

“Hold on?” she asked. She didn’t shriek, but she was having a meltdown, she could tell.

“You got your meds?” he asked.

She did, she had her anxiety meds. She dry-swallowed a gabapentin.

“I . . . I gotta get a flight, don’t I,” she said.

“I’m gonna look online,” Jerome said. “See if I can book you a flight to London from JFK, okay babe?”

“It’s gonna be so expensive! We can’t afford it!” she wailed.

“We’ll worry about that later.” She could hear keys clattering. “I’ve got it. I’ve got it. You’re okay. I got one. It leaves at eight p.m. It’s not so bad. It’s about seven hundred dollars. Well, more like eight hundred dollars.”

“Jer, I’m so so sorry!”

“It’s okay, babe.”

Oh God. Would, like, the FBI realize that she was supposed to be in Austin? She had checked in there. Were they going to think it was fraud? That she was a terrorist? She stayed on the phone with Jerome while she went out through baggage and came back in and checked in at Delta. Thank God she’d been flying American Airlines. Maybe since she was on another airline they wouldn’t notice that she had just been in another city and shouldn’t be able to be here. She kept waiting for someone to say something. Her luggage was on another goddamned plane. What would she say if they said something?

No one said anything.

She told Jerome she loved him and hung up. Then she sat at the gate with her head down and cried.

Nothing happened. She picked up her luggage in Heathrow where it sat waiting in the baggage office. No one even asked why she hadn’t gotten it on the baggage carousel.

She popped gabapentin and floated in a wave of squashed anxiety through her trip. No one said anything about her missed flight when she flew back.

After that, she stopped looking altogether, and if she thought she saw a corridor or a door, she looked the other way. If she thought she saw Lynne (and she thought she saw Lynne a lot, although the few times she let herself really look, it never was Lynne) she walked the other way.

She counted her steps, avoided airport junk food, and stayed in her lane, so to speak.

They got the Dua Lipa project and it turned into a fucking nightmare. Every time she flew to London, she was a wreck.

She started thinking that she was tired of this, tired of traveling so much. The company was doing well, there were more trips, more projects, they hired more engineers. She was promoted to a project manager. The money was better but, on the side, she started looking at job listings on LinkedIn and Monster. She thought about how their townhouse was like a lot of other townhouses, so she painted the living room walls sage and put a wallpaper mural in the bedroom. It looked like a giant eighteenth-century illustration. She’d seen it online on a site called Apartment Therapy. It made the townhouse look different, not like every other townhouse. It helped her stop thinking that some stranger might open the door into their place.

Jerome started talking about marriage. They hashed out that they didn’t want kids. (Jerome, she thought, kind of did. But not enough to fight about it, at least not yet.) For the first time since they’d moved in together, they decided to go on vacation. They chose Maui. And of course, in LAX, Los Angeles International Airport, where they were connecting, Amelia saw a corridor.

She turned so abruptly that Jerome said, “You need a bathroom?”

“No,” she said, “there’s another concourse.”

“You mean, like JFK?” he said.

She nodded.

“Where?” he asked.

“Between gate 21 and gate 23A,” she said.

He squinted. “I don’t see it, Ame.”

“That’s okay,” she said. She kept walking to their gate.

Jerome followed, jogging a little to catch up. “Don’t you want to check it out?” he asked.

She shook her head.

“But it’s your door, right? We can do like you did before. Just look and then come back. I mean, what if it’s Kahului Airport? What if we don’t have to fly?”

“What if it’s Saint Petersburg, Russia and we get arrested?” she snapped.

“Well, it’s always been in the U.S.”

“No,” she said. She found two seats at their gate, sat down, and pulled her roller bag in front of her like a barricade.

“Okay,” he said. “Okay, babe.” He sat down and took her clenched hand. “S’okay. I just wish I could have seen it.”

Really, it made no sense. These corridors, these doors, they just made her feel anxious. She had tried creating an Excel sheet, but she had so little data.

Some things were unknowable. When she was at her first job, working for a little engineering firm that did contracting, her boss, an older woman who wore cardigans and swore a lot and had stories about the good old boys’ club of engineering, had mentored her through her first few projects. One of them had been complicated, novel. Like how to provide access to hidden air filters without any visible fasteners, the trick was to use spring-loaded magnetic latches. Lisa, her boss, had said, “First, list what you know you’ll need to do. Then if there are parts you feel like you don’t have solutions for, list what your known unknowns are. Then we’ll tackle those.”

This whole thing was full of known unknowns. And unknown unknowns, probably. Like physics unknowns—how could this defy all laws of physics?

This was a problem. Like any problem she faced from how to attach LED screens to a façade to how to make Dua Lipa’s people excited about the invisibility of the strings of LEDs that would hang in front of the singer, then come alive with images when they were on, moving just a little, making that image shimmer and ripple.

Or maybe it wasn’t a problem. Maybe it just was what it was. It was linked to her, a part of her. It was hers to deal with or not.

She was used to worrying about consequences. About what could go wrong. She was a development engineer, not a QA—someone whose job was assuring quality—but you couldn’t design things without thinking about how they could work, how they could be put together, how people could do things, and how they might get hurt.

There were a thousand reasons why she should not take Jerome through the door.

But she was sure the door was hers. She could take it. Thing was, this was connected to her in some strange way. She could ignore it. If it made her unhappy, she could choose. She could make it about her, her choice.

They had an hour before their flight.

“What if it isn’t a place like JFK?” she asked. “What if we got stuck in, say, Toronto. How would we get through customs?”

Jerome nodded at her, then pushed his glasses back up. “That would be . . . complicated.”

“Maybe we could just go see if it’s really there. You know, go through, and come right back.”

Now he looked apprehensive.

“I got this,” she said.

They went back down the concourse, roller bags like obedient dogs behind them. “It’s there,” she said. She could see the corridor, and at the end of it, another concourse. People and shops.

“I don’t see anything,” Jerome said. “Are you sure?”

She went closer and he followed.

“What do you see?” she asked.

“Just a wall,” he said. “And on either side, the gate’s windows, and planes. What do you see?”

She didn’t want to choose to ignore. She was afraid, but that was okay. When things were uncertain, fear was normal. When she thought about the world—getting married, politics, the pandemic—it was all uncertain. The thing was not to avoid uncertainty, the thing was to choose. In that moment, standing there with Jerome, she decided. She chose this thing. She chose to walk through, to see where it led.

“Okay,” she said, “close your eyes.” She took his hand. What if he couldn’t go through with her? What if you got stuck somewhere like Turkmenistan or Australia?

She walked through and he followed, eyes closed, trusting. There was a door, and a corridor. She pulled out her phone. “Open your eyes,” she said.

Halfway down the corridor, her phone said it was an hour later, three in the afternoon, not two. They were on Mountain Time. Ahead was a food court with a Smashburger. She checked her location: Boise.

“Oh my God,” he said. “It’s true. I mean, I believed you, but it didn’t feel . . . real.”

“Not the same as having it happen,” she said.

He nodded, still stunned. He was looking at his phone, map app open, and back at the food court.

She took a deep breath. “Let’s go look.”

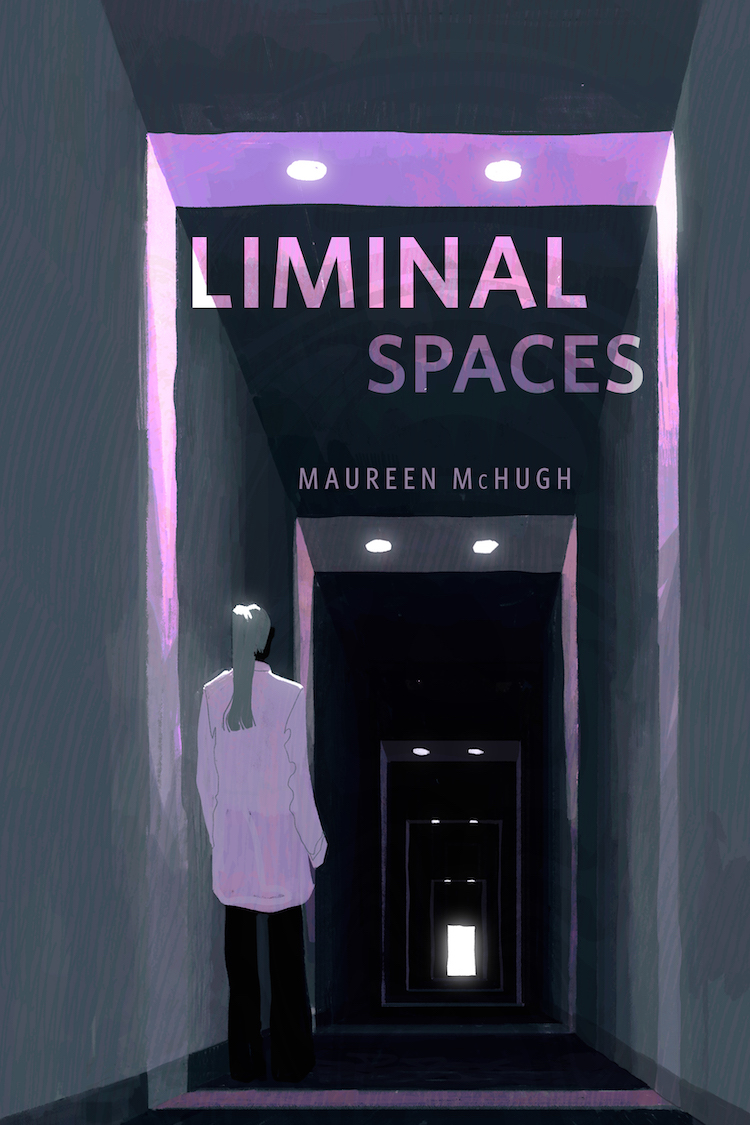

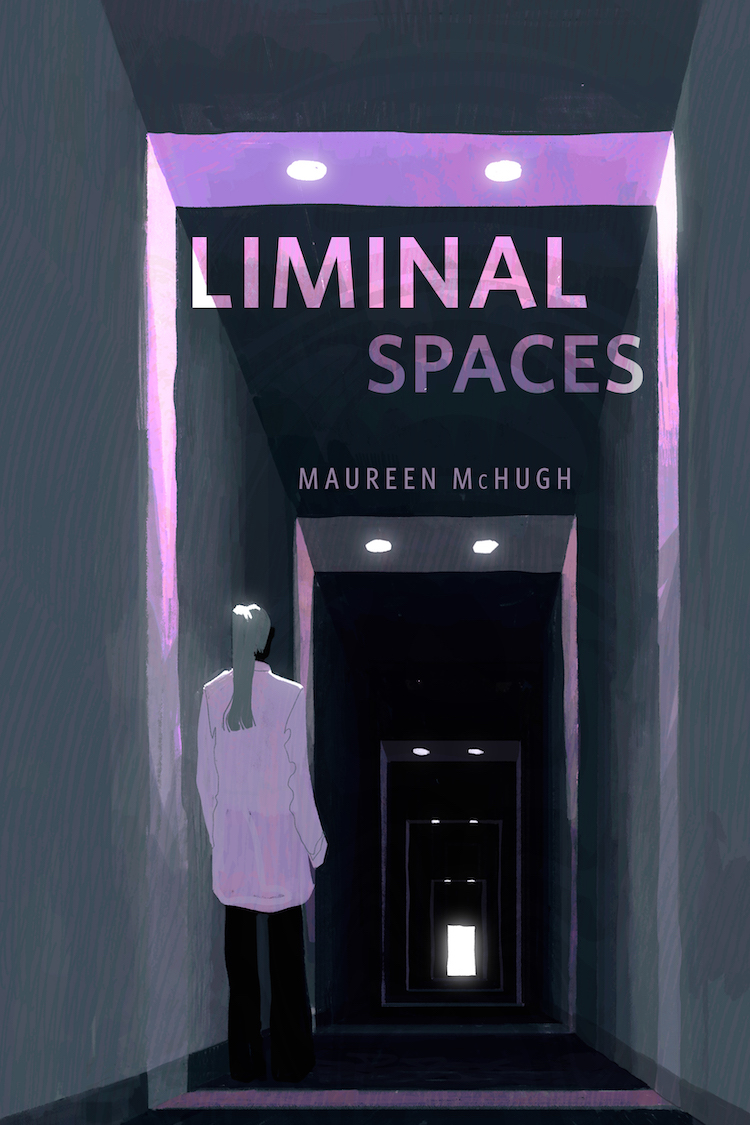

“Liminal Spaces” copyright © 2024 by Maureen McHugh

Art copyright © 2024 by Katherine Lam

Buy the Book

Liminal Spaces